Lisa Banu

(Assistant Professor, Purdue University)

Abstract

This essay follows the legacy of the rickshaw that ranges from 19th century exploitation, to late 20th century expression, to contemporary environmentalism. It presents the early history of the hand pulled rickshaw followed by various subsequent manifestations, as traveling canvas’ for popular cultural expression in Bangladesh, as commercial billboards, as tourist attractions and as sustainable transport. The biography of the rickshaw exposes an evolving political climate with associated implications, from imperialism to democracy. Moreover, the rickshaw maneuvering limited nodes within cosmopolitan circulation functions uniquely in a ‘glocal’ manner. As such, the rickshaw represents contradictions inherent in contemporary cosmopolitan life trying to bridge, global uniformity, individual performance and environmental concerns. The changing narratives of the rickshaw translate an instrument of exploitive human labor to a symbol of sustainable self-sufficient transport. The cycle rickshaw or pedi-cab is an exemplary object representative of a universal mechanism animated by local cultural needs, be it commercial, cultural or personal.

I. Introduction

December 4th, 2006, a BBC News article bid “Farewell to hand-pulled rickshaws” reporting a bill passed in West Bengal, which outlawed the use of the hand pulled rickshaw.[i] Officials supportive of the ban argued that the dehumanizing labor of one person carrying another was long overdue. The continued use of the cycle rickshaw, a mechanized version of the hand pulled rickshaw, prompts the question: when is labor inhumane and when acceptable? Narratives that accompany the use of the cycle rickshaw, at its core speak to this question of ethics. While early hand pulled versions of the rickshaw condoned the status of rickshaw pullers as beasts of burden, mid 20th century discomfort with the ethical burden initiates an expression mode that evolved into late 20th century tourist attraction. Today efforts of sustainable transport systems eliminate the passenger seat or limit passenger seating to children, and extends the philosophy of sustainability to include self-sufficiency. As such, the rickshaw represents the evolving nature of global politics straining between universal human dignity and local needs of survival. Socio-cultural anthropologist Arjun Appadurai explains global disjunctive flow as follows, “[Thus] the central feature of global culture today is the politics of the mutual effort of sameness and difference to cannibalize one another and thereby proclaim their successful hijacking of the twin Enlightenment ideas of the triumphantly universal and the resiliently particular.”[ii] The rickshaw, I argue is an object of global culture and a barometer of urban conditions confronting, labor, self-expression, tourism, performance, environmentalism etc. Sharing in Appadurai’s appeal for a globalization from ‘above and below,’ Bangladeshi Nobel Laureate, Mohammed Yunus, founder of the Grameen Bank, employs the rickshaw as a metaphor for less developed countries in a global flow, as mentioned in his acceptance speech:

I support globalization and believe it can bring more benefits to the poor than its alternative. But it must be the right kind of globalization. To me, globalization is like a hundred-lane highway criss-crossing the world. If it is a free-for-all highway, its lanes will be taken over by the giant trucks from powerful economies. The Bangladeshi rickshaw will be thrown off the highway. In order to have a win-win globalization we must have traffic rules, traffic police, and traffic authority for this global highway. Rule of "strongest takes it all" must be replaced by rules that ensure that the poorest have a place and piece of the action, without being elbowed out by the strong. Globalization must not become financial imperialism.[iii] Yunus’ imagery summarizes the precarious position of the rickshaw, continually challenged in a modern fast paced world. The historical, political, cultural, environmental and commercial themes propel the rickshaw across the globe and reveal it to be transport that challenges the modern imperative of speed and distance, and operates as a site of contest involving labor, environmental, commercial, political and cultural issues. It is to be celebrated that the legal and technological battles across the world that accompany the rickshaw share common concerns related to labor and pollution. Such legal and organized actions show efforts to negotiate globalization from above (corporations, multi-nationals, governments) and below (grass roots activists, collectives).

Interpreted through the perspective of globalization, “the triumphant universal and the resilient particular,” the rickshaw narrates a story of modern life propelled by contradictions of functional transport and expressive form. The following pages chart two manifestations of the rickshaw beyond the 19th century systemic conditions of exploitation towards personal expression and global environmentalism.

II. Exploitation

The global journey of the rickshaw was announced almost 130 years ago, in a New York Times article entitled “The Old and New Japan.”[iv] These newspaper articles are evidence of the provocative role of the rickshaw in Western imagination as a measure of progress and exoticism. The hand-pulled rickshaw suffers a complicated birth characterized by conflicting intents and inventors. Robert Gallagher, in an article entitled ‘Rickshaw and Prejudice’ reports at least five accounts of its historical origin: an American Baptist minister, Jonathan Goble or Scabie in 1869; three Japanese smiths in 1868, another Baptist minister in 1888, Albert Tolman, a black smith working in Worcester, Ma in 1848 and an out of work Japanese Samurai.[v] Of these five, the first two offer most evidence. Whether it was a westerner adapting to Eastern conditions or Easterners adapting western practices to local context remains obscure. At its very origin the rickshaw presents a paradox of motives and sources. To further cloud the origin, there are also suggestions of earlier European versions as evident in medieval paintings of Italian vinegar carts or illustrations of the French Broutte.[vi] However, the wide use of the rickshaw is clearly evident during the emergence of modern Japan. According to legend, Jonathan Goble a Baptist minister invented the rickshaw in order to transport his invalid wife through the streets of Yokohama. This story allows, to a certain extent, a sympathetic and possibly justifiable use of human labor.[vii] The charitable birth of the rickshaw compounded by the hybrid cultural construction reflects the rickshaw’s inherently complex motivation. Components such as religious, therapeutic and western contexts of this story sanction the origin of the rickshaw with moral authority. The ex-patriot American who utilizes mechanical ingenuity towards transporting his invalid wife offers a moral accent for an otherwise suspicious mechanism. In this case the argument of improvement follows that instead of palanquin, which requires at least two carriers, the rickshaw reduces the labor to one and maintains a chair posture more comfortable for the rider. There is also an underlying combination of gender frailty and illness that supports the story. In sum, the Jonathan Goble story implies that the rickshaw, intended for women and the weak, reduces labor from two carriers to one and increases rider comfort. As a product of Western imagination and ingenuity, the jin-rickshaw or ‘man-powered’ vehicle follows an ethical and progressive logic. The Japanese account, on the other hand, maintains a simple commercial logic. It identifies three men: Izumi Yosuke, Suzuki Tokujiro, and Takayama Kosuke, who inspired by the newly introduced horse drawn carriage, develop the rickshaw as an alternative in 1868.[viii] The ‘man powered vehicle’ is premised on the efficiency of a single carrier in contrast to multiple carriers of a palanquin. In addition the rickshaw replacing expensive horses was simply cheaper. The narrative of native appropriation of foreign technology (in the form of horse drawn carriages) exhibits Japanese innovative spirit and active engagement with the West. Three components of this story are important: multiple inventors, replacement of expensive animals and transformed Western technology. There are suggestions that there was direct involvement of the Japanese government in regulating the production of the rickshaw. A 1993 United Nations report titled “ Technological innovation and the development of transportation in Japan” explains, “ In April 1870, permission was given to operate rickshaws, a traditional cargo cart modified to carry passengers. Human-powered carts like these were easy to use and did not go very fast, making them well suited to the roads at the time; indeed, by the early 1880s, 25,000 rickshaws were in operation.”[ix] The story that replaces expensive animals with cheap human labor remains to be verified by an official Japanese narrative. While this story of replacement is suspicious, it nevertheless provides a counter point to a unilateral claim of foreign invention. The several online accounts of rickshaw history that follow the same dual account or origin offer consensus but not documented proof. Accordingly, both of the above stories should be considered with a healthy dose of skepticism, as presently I found no clear evidence for either. Despite the opacity of origin, the rickshaw is discussed in considerable length in the New York Times article entitled, “The Old and New Japan” (printed August 10th, 1877):

Japan is indebted to an American, if I am correctly informed, for one of the curious spectacles it presents to strangers. Down to seven years ago the modes traveling on land were not numerous. You could walk, you could be carried by men, or you could ride on horseback. There were good roads and streets but no wheeled vehicles, with the exception of a few clumsy concerns of snaillike velocity. A sharp-eyed American—I wish I knew his name--- invented, in 1869 or 1870, the jin-riki-sha, or man-power carriage. It is, as its name implies, a vehicle drawn by human arms, and very good speed does it make. It is like a tow wheeled chaise, newly hatched and just from the shell, or a baby cart of more than ordinary proportions.[x] The article continues with an account of the reporter’s experience on a rickshaw and also the production and the use. In order to contrast the old and new, the rickshaw and the railroad is juxtaposed, despite the concurrent use and development of both technologies. In describing the rickshaw the author congratulates the unnamed American inventor, the experience as a rider, the impact on city streets and a comparative context of the railroad. The report confirms the use of the rickshaw in Japan during the industrial revolution. While the narratives of therapeutic and commercial intent describe the production of the rickshaw, the New York Times report is evidence of local reception and Western critique.

The ironic inception of the rickshaw at the dawn of the industrial revolution represents contradictions inherent in industrialization, modernization and globalization in the East. Neither modern nor traditional, the rickshaw represents a mediating agent open to multiple political, economic and cultural incarnations. Amidst all the confusion, it is however clear, that the rickshaw is decidedly an urban phenomena dependent on a density of population and destinations. Weaving through urban fabric, the rickshaw has the potential of translation into urban environments across the globe. Slow, compact in congested roads, convenient for short distances and cheap, the rickshaw permits a level of spectator experience similar to Walter Benjamin’s Parisian ‘flaneur’ in the context of the East.[xi] The spectacle of the rickshaw persists throughout its evolution. Increased urbanization increases the use value of the rickshaw while increased concerns of inhumane labor decreases its symbolic value. Despite the indeterminate birth, the rickshaw travels quickly beyond the islands of Japan. Chinese merchants carry it to India and Singapore in order to carry merchandise, soon permission is granted to carry people as well. In each of the three places, China, India and Singapore, the status of the rickshaw runner not the mechanism draws attention. Supported by this urban class of runners, the rickshaw develops into a mass transit system. The concurrent development of a class structure and an urban transport structure soon erupts into various runner strikes across the East. As an instrument of political organization the rickshaw represents a new class of urban labor. A cloud of exploitation hovers over the rickshaw as it spreads across Asia.

In Singapore, for the first time, the rickshaw transforms into a metropolitan scale transit system. The intensity of its use, powered by Chinese labor galvanizes runners into a political force. Consequently, the ethical question of dehumanizing labor festers into political unrest. Early twentieth century ethical and political concerns are evident in the article “Social History and the Photograph: Glimpses of the Singapore Rickshaw Coolie in the Early 20th Century” by Jim Warren as well as the book, ‘Beijing Rickshaw’ by David Strand.[xii] The novelist Lao She’s ‘Rickshaw Boy’ that follows the plight of a rickshaw runner in China (made into a movie in 1982) also attests to the symbolic power of the rickshaw as representing an unfair social system in which a privileged few are quite literally carried by the laboring masses.[xiii] David Strand explains the symbolic confusion surrounding the rickshaw, as follows, The success of the rickshaw as a mode of transportation and as a means of signaling status led to the vehicle’s prominence in contemporary political and literary rhetoric. For a modern invention, the rickshaw had some peculiar effects. In a sense, the rickshaw represented technological progress, since pulling one was easier than bearing a sedan chair. Over short distances the rickshaw was faster than some kinds of traditional wheeled vehicles, such as the heavy, slow moving mule cart common to north China. But at the same time, instead of simply substituting machine for animal or human power, the rickshaw also intensified the need for the most strenuous physical exertion. A walking puller saved steps for his passenger. A running puller saved time. The market duly rewarded the swiftest and strongest and created the spectacle of poor men straining to pull a largely middle class clientele. Not only did the rickshaw become a popular method of conveyance in cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Hankou; the sight of one human being pulling another also became a symbol of backwardness and exploitation.[xiv] Among other factors, rising class-consciousness of rickshaw runners fuel political revolution that eventually leads to the communist government’s ban in 1949. In a strange twist since the 1990s, the rickshaw has returned to Beijing as a tourist attraction to the dismay of old revolutionaries. What was once a symbol of bourgeoisie oppression has now diminished into a job, just like any other, into capitalistic commercialism.[xv] In another twist of irony, political mobilization of the rickshaw pullers succeed in exposing harsh labor and in turn, the legislative success ends their livelihood. Alternate employment remains an unresolved issue in India, where the hand-pulled rickshaw was relatively recently banned. The novels ‘Rickshaw Boy’ and ‘City of Joy’ both offer accounts of the oppressive system of rickshaw labor that was akin to indentured servitude. The harsh reality of urban labor is juxtaposed in India where the colonial context heightens romantic exoticism already evident in the early days of the rickshaw in Japan. In India the rickshaw is first adopted in Simla, and then Calcutta. Here it becomes a vehicle of colonial romanticism as evident in Rudyard Kipling’s short story, “The Phantom Rickshaw” in which the protagonist sees apparitions of his dead and jilted lover riding the streets of Simla. The rickshaw, in the context of romantic love and nightmares, captures western imagination as the native vehicle into the exotic. Again associated with a wounded woman, the rickshaw combines concerns and fear of the ‘weak.’ In India, the colonial context, unlike China, adds a cultural component of foreign-native contact. Consequently, the hand-pulled rickshaw acquires an exotic air embellishing the stale odor of exploitation. In this context, the sovereign-subject or colonists-native hierarchy justifies human labor. This link of exoticism continues to be employed in the use of the rickshaw in tourism and maintains the its original east-west hybrid status. Furthermore, an association with entertainment and tourism makes the hand-pulled rickshaw and currently the cycle-rickshaw a cultural performance.

In India, as in China, political discomfort with the status of the rickshaw pullers persists alongside the romantic exoticism of the ride. Among other movies, the 1992, City of Joy highlights the harsh conditions of rickshaw pullers in Calcutta, and serves to assist the eventual ban on hand pulled rickshaws. As the December 4th, 2006 BBC report states,

Westerners try to associate beggars and these rickshaws with the Calcutta landscape, but this is not what Calcutta stands for. Our city stands for prosperity and development,” West Bengal Chief Minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya told journalist recently. “This inhuman mode of transport should have stopped years ago,’ said the communist mayor Bikash Ranjan Bhattacharya. “We can’t imagine one man sweating and straining to pull another man.[xvi] Remarks by the minister and mayor repeat the communist ideological argument against the rickshaw that ended its use in China. The remarks also argue that the hand-pulled rickshaw corrupt an image of a prosperous and progressive Calcutta. As an instrument of human exploitation and impediment to social progress, the life the hand-pulled rickshaw officially ends with local legislation and global media attention

III. Expression

Figures 1 a & b: Rickshaw in Dhaka (Photographs by author)

The political narrative weaves into a cultural narrative in Dhaka, Bangladesh where the proclaimed city of rickshaws uses the vehicle as a medium for political and cultural expression. The surface treatment of the rickshaws becomes the subject of much study. Most notably anthropologist Joanna Kirkpatrick’s ‘Transports of Delight’ offers a robust and historical account of the rickshaw art production. According to Kirkpatrick, rickshaw art operates as a barometer of public opinion as well as a canvas for permissible voyeurism in a Muslim society.[xvii] Owing to great interest both foreign and local in rickshaw art, imagery inspired and related to the practice has developed into an industry that feeds a taste for the familiar made exotic. (See figures: 1 a & b) Indeed, imagery both of and on the rickshaw has become symbolic of Bangladeshi popular transport, culture and nationalism. Even though it has reached iconic status as a national symbol, the rickshaw is very much suspect in World Bank efforts to industrial and modernize Bangladesh as evident in a 2004 recommended phase out.[xviii] While the political question of human labor persists as in the rest of the developing world, in Bangladesh, the cycle rickshaw is also subject to accusations as being the source of crippling traffic congestion. The rickshaw is barred from major highways but permitted on smaller streets. The marginalization of the rickshaw serves to frustrate both drivers and riders suffering long detours. The current contradictory status of the rickshaw as national icon that hinders international development is representative of a local and global disjunction that Appadurai alerts of, by citing the need for globalization from both ‘above’ as in institutional structures and ‘below’ as in grassroots movements. The confrontation of the modern impulse to standardize the global resilience of the particular erupts into a battle of international development organizations and local needs.

Figure 2: Images with permission of Mainstreet Pedicabs

New York City and the Commercial Spectacle of the Pedicab

While in Bangladesh the rickshaw is a signboard for popular culture and transport for the economically downtrodden, in NYC the rickshaw is a commercial display for corporations and transport for the economically comfortable. In NYC, it sheds the stain of poverty and instead becomes a tourist attraction and advertising space for ‘youthful’ companies such as Gap, Banana Republic and Target. Corresponding to the shift in use, the status of the pullers also shifts from laboring to performing. According to Steve Meyer, owner of Mainstreet Pedicabs, a Colorado based pedi-cab manufacturing company, “The drivers typically make a lot from their pedaling, but also their personalities.”[xix] The conversion from labor to performance recovers an experience of childlike fantasy and pleasure, long suspect under an ethical burden. In NYC the pedi-cab becomes the global version of Walter Benjamin’s Parisian ‘flaneur’ experience, where the riders experience the city in motion, in observation and possibly in conversation.[xx] A dual performance the horse drawn carriages cannot accomplish. Much like in China, the free market choice to both operate and ride a pedi-cab alters the perception of exploitation. The commercial re-branding of the rickshaw as in NYC pedi-cabs, would be complete if not for the recent controversy related to license limitation. As recent as April of 2007, a New York Times article title read “ Pedicab Limit Withstand’s Mayor’s Veto,” suggesting a political victory against pedi-cab operators and Mayor Bloomburg, in favor of capping the number of pedi-cabs to 325.[xxi] Mayor Bloomburg originally in favor of the legislation, after hearing testimony of pedi-cab operators decided to ‘let the free market decide’ but also suggesting that he may be amenable to a cap of 500. The appropriate number of pedi-cabs on city streets is as contested in NYC as in Dhaka, although the implications are very different. The pedi-cab as an agent of free market commercialism acquires a currency of public demand and opinion in NYC beyond serving as substitute public transport, as in Dhaka. In both Dhaka and New York City the rickshaw performs as an urban spectacle. Although, in Dhaka, in addition to being an urban spectacle the rickshaw provides a system of mass transit otherwise absent. Variations of the cycle rickshaw demonstrate particular expressions of a universal need for efficient transportation, cultural and commercial expression. The contexts of Dhaka and New York City present a spectrum of cultural significance. Moreover, legal and international discussions surrounding the use of the cycle rickshaw are also testament to its public role towards cultural expression and popular need. The modern death of the hand-pulled rickshaw is succeeded by the contested global life of the pedi-cab. The next generation following the hand-pulled and the cycle rickshaw, continue the imperative towards easier labor and cleaner fuel. As such, the newest generation of pedi-cabs can be characterized as in service of an increasingly local-urban community, as clean powered and as vehicles of personal expression.

IV. Environmentalism

In order to address the problems of inhumane labor and slow pace, efforts motivated by an alignment of human rights and clean, sustainable environmental practices characterize current incarnations of the rickshaw. For example, solar powered cycle rickshaws have been announced in India this February that can run up to 60 to 80 kilometers per charge with speeds of 25-30 km per hour.[xxii] According to the article, each solar powered rickshaw unit can save 10 tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually. This June, another article announced, “Bangladesh Rickshaws get modern makeover’.[xxiii] The make over conducted by the army aims to revolutionize transportation in Dhaka through the use of rechargeable battery powered electric rickshaws while retaining the beloved cultural form. Major Mahmud’s explanation that the rickshaw will travel up to four time faster and lesson the physical strain on the pullers, addresses both concerns of inhumane labor and slowness. For comparative reference, in 1998 an estimated seven million passenger trips were made in Dhaka, covering 11 millions miles, double the output of the London underground. The significance of a rickshaw ‘makeover’ can hardly be understated. The involvement of the army in the development of an improved rickshaw system attests to the significance of the rickshaw in national consciousness. Consistent with the cultural statement of Bangladesh, the environmental statement in Europe has generated a culture of global, environmental and ethical awareness. The commercial and environmental arguments converge in Europe and fuel interest in efficient and ethical adaptations of the mechanism. Concerns regarding appropriate number of pedi-cabs on metropolitan streets, aiming to set our toleration level for the slow in fast cities, appear across Europe. For example, in England as of 2003, 350 pedicabs were in operation in London and continue to be a source of debate on traffic safety. During the last two decades, various European countries have adopted the rickshaw as a pollution free alternative on a limited scale.

Negotiations of cultural, ethical and environmental demands characterize the contemporary rickshaw in Dhaka. In India, Bangladesh and elsewhere, the environmental movement has served to consolidate the political, economic, cultural perspectives in order to work towards a global environmentalism that combines human empowerment and ecological sensitivity.

V. Conclusion

The evolution of the rickshaw from hand-pulled to cycle, depicts changing historical and geographical contexts but more importantly changing ethical concerns. At its core the evolution shows our answers to the question: when is labor inhumane, when acceptable? The 19th century functional hand pulled cycle accepts labor of one to carry another. The 20th century expressive cycle rickshaw adds creativity to the labor. The 21st century pedi-cabs of sustainable transport begin to limit the passenger seat, whereby the driver is also the primary rider. From laborer, to performer, to rider, the shift marks the transformation of the rickshaw puller to rickshaw rider. Each re-branding of the rickshaw, repurposes the mechanism to fit the ethical environment, as well as historical, technological, geographical, cultural, commercial and political concerns. The context of globalization brings all these perspectives into confrontation. The 19th century struggle of standardizing labor was hierarchical. The 20th century cycle rickshaw attempts to subvert the hierarchy with creative resistance. In contrast, the 21st century pedi-cab strains to become an alternative to hierarchical standards of mobility. This brings us back to Appadurai and Mohammed Yunus’ articulations of things in conditions of globalization, whereby the universal is neither sustained nor subverted by the particular. Rather, the particular asserts a parallel and almost self-sufficient mode. The pedi-cab combines tourism, performance, display with transportation, as an alternative to mere fast and functional cars, buses, subways of everyday.

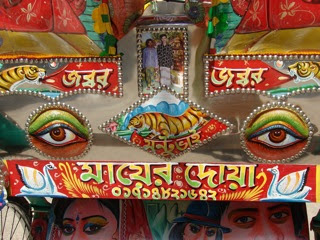

Figure 3: Rickshaw detail with photograph and phone number of owner/operator, photograph by author

By way of conclusion, let us consider the image above that reflects the status of the rickshaw from the perspective of a puller/owner. The back of this rickshaw in Bangladesh contains, movie images, a phone number, a photograph, the signature of the rickshaw designer (Monto Bhai) and the phrase ‘Mother’s blessing.’ The collection of images that serve to personalize the rickshaw is evidence of a strong sense of ownership and identity. The rickshaw here no longer represents oppressive labor for another, in either terms of passengers or rickshaw owners. Rather, it shows active choice in the signature, photograph, phone-number and images. For the owner it is an expressed blessing. An object historically associated with oppression here transforms into an autobiography in motion, in display and in celebration. Our opening question of acceptable labor practices that the rickshaw engenders, finds one answer here. Rickshaw evolution articulates human freedom against human labor towards human expression. By translating the rickshaw from a functional object powered by labor towards an expressive object driven by imagination, freedom shows itself as an inherently artificial creative condition beyond biological necessity. In the era of globalization it presents a shared ethical direction towards universal human empowerment reached through diverse vehicles traveling in creative ways.

Contact - lsbanu@purdue.edu

Notes:

[i] Subir Bhaumik, “Farewell to Hand-Pulled Rickshaws, “BBC News 12/4 (2006). [ii] Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 43. [iii] Yunus, Nobel prize acceptance speech (December 10, 2006) [iv] “Old and New Japan” (New York Times, August 10, 1877) [v] Robert Gallagher, "Rickshaw and Prejudice," Himal 10, no. 1 (1997). [vi] As evident in a painting by Claude Gillot, Les Deux Carrosses, 1707. [ix] “Technological Innovation and the development of transportation in Japan,” (United Nations University Press, 1993) [x] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Belknap Press, 2002) [xi] David Strand, Beijing Rickshaw: City People and Politics in the 1920s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993) and Jim Warren, “ Social History and the Photograph: Glimpses of the Singapore Rickshaw Coolie in The Early 20th Century” (Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1985) [xii] David Strand, Beijing Rickshaw: City People and Politics in the 1920s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993). [xiii] Lao She, Rickshaw Boy (University of Hawaii Press, 1979). [xiv] Strand, Beijing Rickshaw, 35-36. [xv] Miro Cernetig, “China’s Rickshaws Bring Back Bad Memories” (International Herald Tribune, 1999). [xvi] Subir Bhaumik, “Farewell to Hand-Pulled Rickshaws,” (BBC News 12/4/06) and “Calcutta Plans Ban on Rickshaws,” (BBC News 8/15/05). [xvii] Joanna Kirkpatrick, “Transports of Delight. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003. [xviii] World Bank report in Sharifa Begon and Binayak Sen, “Pulling Rickshaws in the City of Dhaka: A way out of Poverty?” Environment and Urbanization, no. 11 (2005). [xix] Steve Meyer, Owner of Mainstreet Pedicabs, email correspondence. [xx] Micheal Wilson, “He caters to a Brooklyn Kind of Carriage Trade,” New York Times, September 29 (2007) [xxi] Jonathan Hicks, "Pedicab Limit Withstand's Mayor's Veto," The New York Times, no. April 24 (2007). [xxiii] Shafiq Alam, "Bangladesh Rickshaws Get Modern Makeover," Dawn 26/6/2008 (2008).